How Growing Up in Yugoslavia Colors My View of Confession in Art

On privacy and censoring oneself

I recently read a couple posts about confessional poetry that inspired me to throw in my five dinars. Yugoslavia was a socialist country where those with professional careers attended the church of the communist party, while those who only had private lives could tend to religious customs if they so chose. When I think of confessions, I think of sacrificing something precious. What does that mean for poets and artists?

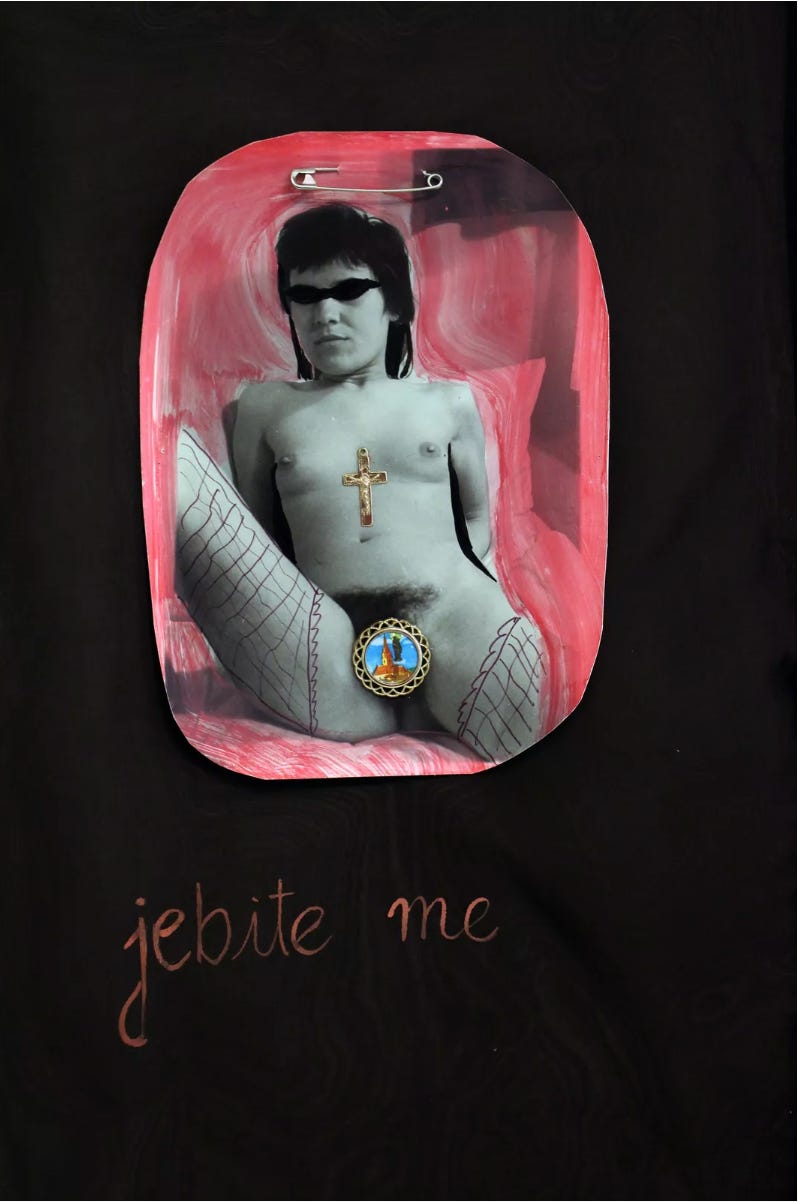

Confession implies guilt, an acknowledgment of sins, or an admission of transgressions. At its core, it requires self-examination and divulgence of a hidden, often shameful truth. Confession also evokes private spaces, either whispers uttered in the cool semi-darkness of a confessional booth or tense silence in a neon-lit interrogation room.

Confessional verse of the ’50s and ’60s didn’t chase absolution nor answers. It sought release. But there is this other, more enduring poem (and other forms of art) that continues to investigate the interior. What does that art seek and sacrifice?

A poem straddles the private and the public. Reading a poem is an intimate experience, yet poetry is also performed. Same goes for art—it feels intimate, yet it’s made for display. There’s a dialogue, then, between our sense of the private and how we respond to art that reveals the self.

America loves privacy. This is a vast country with massive roads and shopping centers, sprawling suburbia, limited public transit, and an infrastructure that discourages regular close contact. The cost of all that space, in my opinion, is isolation. And I wonder how much that isolation feeds a desire to reveal the self and make oneself known to another.

The relationship to privacy is different in places where people live in close quarters. Masks come off fast. Private moments are more visible. Economic status shapes this, too, and poverty especially tends to kill privacy. The flaws of the poor are more visible. I have no idea what it’s like to be rich, but I know what lacking space feels like. As kids, my sister and I lived with our parents and our Irish Setter in a 500-square-foot one-bedroom on the 9th floor of a tower block, until Dad Macgyvered it into a two-bedroom with a tasteful plywood partition. Early on I learned to honor my need to be alone.

Regardless of the comfort of our lives, as artists we always negotiate how our private lives and experiences factor into our art. Here are some of my thoughts.

I was raised in former Yugoslavia, now Croatia. I emigrated in ’97, a couple years after the war in Croatia ended, at the age of 21. I’ve spent most of my adult life in the US. While my bio says I’m Croatian, my cultural identity is mixed. What does this have to do with confession and disclosure in art? It’s a reminder that interiority is layered and that labels fall short. We can choose to call a poem confessional, but it’s rarely just that. Art is not a set of categories but ideas expressed through disciplines, genres and materials. Artists are first and foremost thinkers. And their ideas always come before classifications and labels. And while our backgrounds shape how we perceive disclosure, we ultimately need to stay open to what might not resonate right away.

Like all Yugoslav children starting school, I pledged allegiance to Tito and became a “little partisan.” (Partisans were freedom fighters who fought the Nazis.) Here is a rough translation of the pledge: “Today, as I become a pioneer, I give my solemn pioneer word to work hard, be a good comrade, love our homeland, and uphold the brotherhood, unity, and ideals Tito fought for. I promise to honor all people around the world who strive for freedom and peace.” I’m not one for committing to ideologies, but this makes me wonder what set of principals a poet or artist is ultimately loyal to? Commitment to practice? Or commitment to a mode? What does the performance of our commitment look like?

I’ve written poems about war. I’ve also written about sex. And I’ve written work based purely on research. I can’t help but write from experience as well as from what interests and haunts me. But regardless of what my work is informed by, it is ultimately the product of my imagination shaping my inquiry. It doesn’t serve us to be precious about private matters, no matter how ugly they might be. Frida Kahlo painted her struggles with health. Louise Bourgeois explored her personal life through sculpture. And the reason we love looking at their work is that it offers much more than disclosure. Their art bears witness. It is a curious, imaginative record of an intensely private world.

The extent of my Catholic education is my grandma teaching us the “Anđele čuvaru mili,” the guardian angel prayer. This was on weekends, when we visited the island my dad was from. I was never made to attend Sunday mass. For me, church rituals, including confession, were a backdrop to the communist set design. Their function seemed primarily decorative. Still, church aesthetics shaped how I see the private. I love the symbolism of the booth, as well as murals of saints, their bodies depicted in tranquility, agony, and ecstasy. And while this is not unique to religious art, its placement in churches meant that ordinary people without access to museums could look at art and be moved by it. Now, what happens when a child has no contact with bare human body in art? What happens when their only exposure to suffering is not mediated by art?

There was little to no censorship on nudity and sex on Yugoslav media. On the two state-run TV channels we had, we regularly saw the human body—naked, old, young, imperfect, non-enhanced. Later, during the war, the news showed footage of brutally tortured victims. In the theater of war, the dead had no privacy.

My dad was a devout nudist and as a family we’d go to the nudist beach. (Yugoslavia was a destination spot for FKK enthusiasts in the ’70s and ’80s.) For me as a kid, these were obligatory, boring and uncomfortable hours, not because of naked people wandering the cliffs and floating on canvas inflatables, but because the sunbathers were primarily older folks, and the rocks on which we’d lay our towels poked sharply into our flesh. Dad would get furious at the peep of my sis or me feeling uneasy. After all, he performed his naturist role and with it, we as a family were to be chill about having our asses poked by rocks and thistle. I have strong feelings about privacy and none about nudity. Nudity is a mask, too. As is confidence.

My mom worked as a nurse. I watched her care for many, including my dad’s mother dying of uterine cancer and her own father dying of lung cancer. I still remember the medicinal smell of their bedrooms. There was never shame in the body itself, only attempts at preserving dignity. I wish I had a camera to record it all.

My grandmother had an open casket funeral. Dad insisted on a photographer. He wanted to document the goodbye.

There was no photography at Dad’s funeral. His death was sudden and premature. After the burial, we discovered poems he had written to his estranged first daughter. We didn’t know he wrote poetry. He is the reason I started writing, not just because he encouraged my reading habit and education, but because of our fraught relationship. Yet there is much about him that I still hold myself back from writing about. I’m not ready to suffer the death of ego.

The impulse to share or withhold, weather privately or publicly, is always negotiated and often political. The personal is as valid a subject for art as any other. In sacrificing privacy, the artist becomes an object. Confession is also a concept that can be pushed and expanded. It’s a tool, too, one that isn’t meant for telling the literal truth but to seek a deeper, more poetic truth that we all sense.

Admire the flow of your thoughts, as usual! Always interested to hear about your experiences as a lil naturist. Here, I get a fuller picture--funny but also "piercing"....I'm wondering about the confessional poetry posts that you read and also whether that word "confessional" should be updated--or has it been in some way that I don't know...