Milan had a dark olive complexion and buzzed hair. His face was hypnotic and his head round like the glass marbles he played after class. When school let out, he and his buddies flew downstairs, fast like bats, skipping across the rail, to hang by the basketball court. They reached into their pockets for marbles, then squatted around the little hole in the ground. I watched him by the rail, disguised by the sea of kids filing out of the building, holding a little love note. I wrapped the note around a rock and launched it in the direction of his dusty sneakers. But ever the bad shot, I hit his head instead. As he screamed, I slipped between the shrubs and linden, like a shadow, butterflies leaving my stomach.

I still remember him kneeling in that dusty patch of dirt, cute and distant as a planet. Some images stay with us. Sometimes we can trace them back to specific memories. Other times, we go back to an image without a clue where it comes from.

Last year I resumed painting after ten years of focusing on writing. My latest book was coming out, and I was starting to write a new one. Usually, I write individual poems until I have enough for a cohesive book, but this time I wanted to work on a collection more intentionally. To do that, I needed to find the guiding principle for this emerging work. I could sense it was there, beneath the surface, but I couldn’t articulate it. So I put writing aside for a bit and picked up the old painting supplies.

In the past I had painted in my garage studio on large canvases. Now, I was working at the kitchen counter in my apartment. I painted every night for months, mostly small mixed media studies. Painting daily allowed me to experiment without worrying whether the finished pieces looked aesthetically pleasing. The routine felt meditative, like going for a swim.

I don’t look at references when I paint. I’m self-taught and work intuitively. So, I was intrigued when I started noticing images appear in my abstracts. They looked like details of imagined geographies. And they reminded me of dreams of unknown places, like this recurring one: I’m walking down a curvy sidewalk, crossing a street on the left, then continuing along the beach, pebbles under my feet, and after passing a bend with a large rock on the right, I enter a deep, marble-white cave. I’ve dreamt this cave enough times that it feels like visiting an old home.

Once I started noticing imagery in my abstracts, I assumed they were traces of memory, whether real or imagined. But the more I painted, the more that shifted.

My last book cover is a digital collage of a woman simultaneously disappearing into and emerging from the sea and sky. The poems navigate in-betweenness, living between cultures and languages, and, as Roberto Tejada said, “the disorienting terrain of self.” The cover artist captured the heart of the book in a way that helped me understand what I had been working on. Sometimes an image captures complex ideas with striking simplicity.

When I paint abstracts, contours and images emerge without my intention. I don’t will them into existence or consciously draw them from memory. I look at the shapes that the paint forms, and the images reveal themselves. I can’t dismiss them as chance, though, because we can only see what we already recognize. It feels like I’m tapping into the unconscious, or whatever it is that makes my hand move and my eye perceive.

As I move between painting and writing, I notice that the images in my poems share a certain embodied quality with those in the paintings. There are body parts, breasts in particular, boats, hazy cities disappearing in branches of trees, figures facing each other in endless conversations, usually in pairs, and often shaped as the Glagolitic (old Slavic alphabet) letter Ⰰ. Certainly the inner images are of the same family.

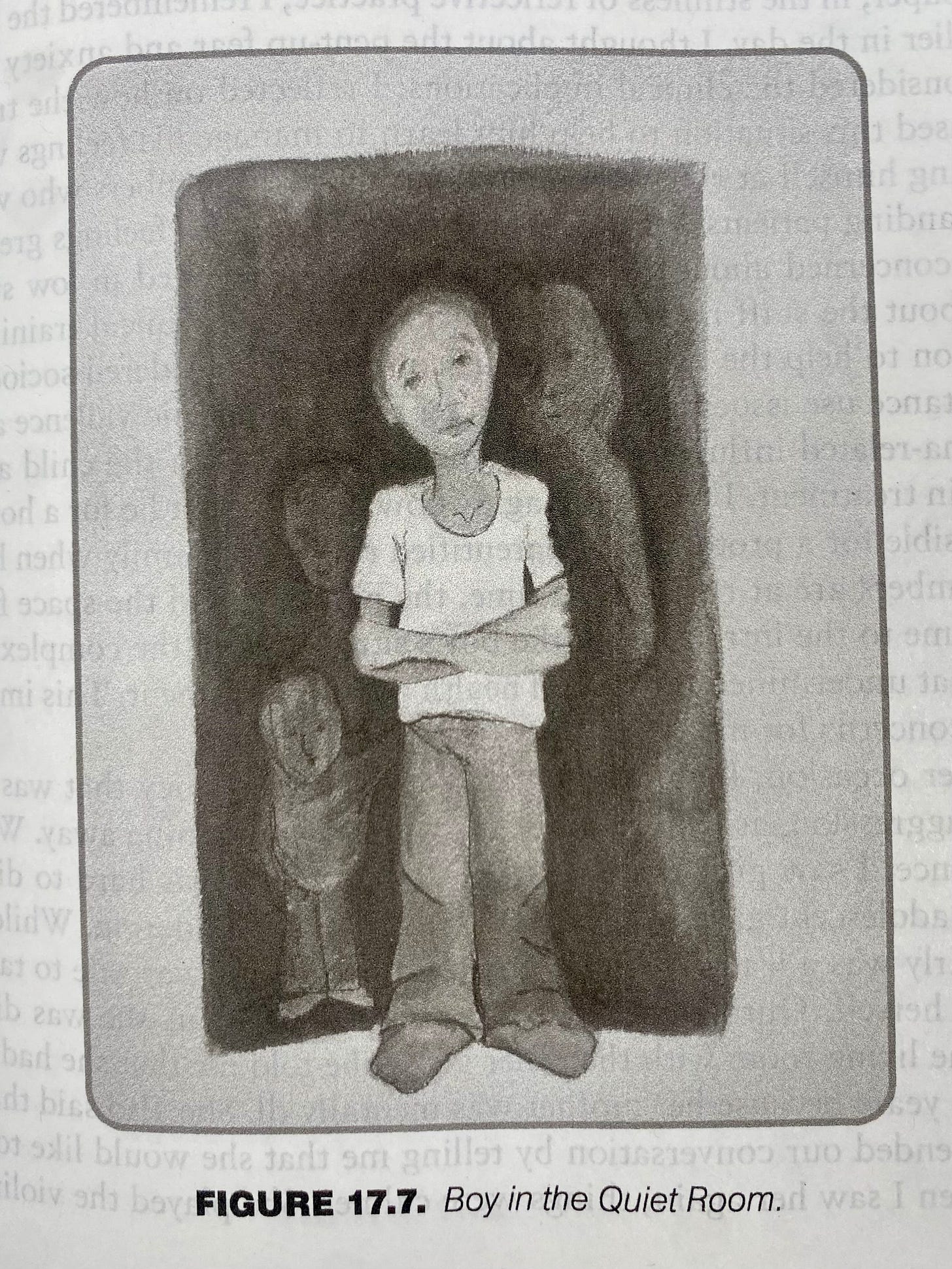

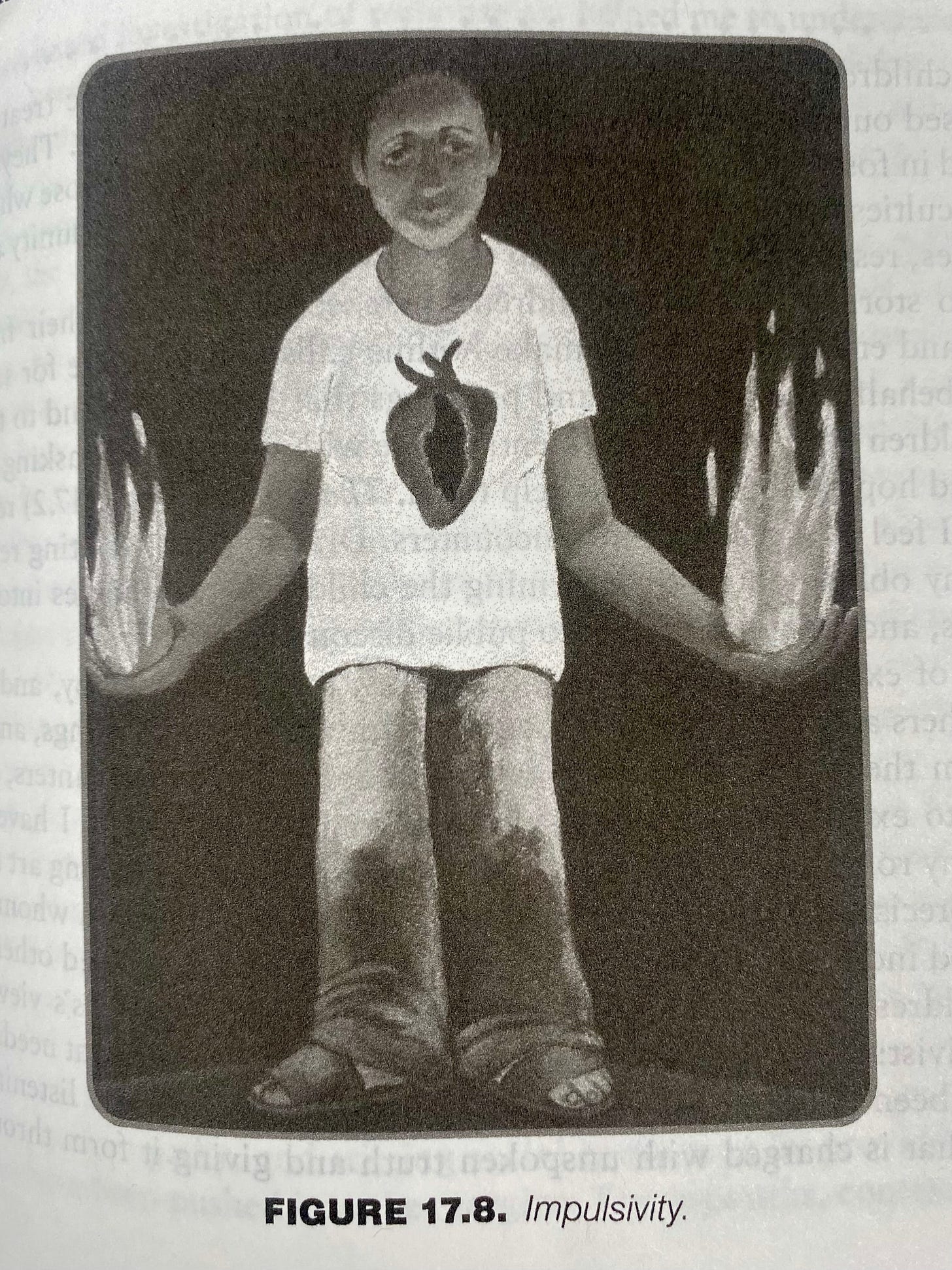

Handbook of Arts-Based Research, edited by Patricial Leavy, contains a chapter “Drawing, Painting, and Story as Research” by Barbara Fish. Fish describes using painting to investigate her own work as a children’s art therapist. She uses response art “as data” to inform her work. The metaphors in her imagery help her understand the children she works with. Her process is fascinating. She places the image at the center of the inquiry and conducts interviews with it.

“For this part of the process, I placed the image in front of me and sat quietly with the intention of being receptive to information that the image would ring. I asked the piece to engage with me in imaginal dialogue (McNiff, 1989) and transcribed the interaction without censoring it. Next, I audiotaped the transcript as I read it aloud. What followed varied for each piece. I stayed open to the unfolding process, following my inklings and the image’s directions as they occurred to me during the interview. This led to more image making and other creative work. Some pieces directed me to paint other images; others asked to read texts. Finally, I evaluated the interviews through pattern analysis to reveal salient themes. The inquiry led to my conceptualization of response art as it is used in art therapy; imagery used to contain, explore, and express clinical work.” (343)

As I read this, I wonder about artists (both visual and literary) having conversations with images in their own work. When explored with intention, an image can be a valuable conduit for insight. An image is more immediate than an idea because it’s not constrained by the logic of language. Perhaps “interviewing” our own imagery could help us identify the unconscious channels we’re drawing from and address roadblocks—how to resolve a messy manuscript, for instance, or how to handle a writer’s block. This approach might lead to a more complex and multifaceted understandings of ourselves and our work.

Fish works primarily with “minority children who are wards of the state, residing behind closed and locked doors of residential programs and psychiatric hospitals.” She says, “People talk about giving those who are marginalized a voice. I believe that everyone has a voice; what many don’t have is a forum. If you can’t hear someone’s voice, you are not standing close enough.”

Her work is fascinating, and I can’t help but apply it to creative practice. After all, aren’t artists wards of their own mental states? So, it doesn’t hurt to ask: What might I need to draw closer to? What might I be flinging love-note-wrapped stones at when I could simply get closer? Not to the boy. Or the thump on his skull. Closer even, to the hand throwing the stone. The hand writing the note. Aiming for affection. Him in submission.

And that note, unread, crumpled under the shuffle of his feet.

Starting October 8th, I’ll be teaching a 6-week advanced poetry writing workshop through Writers.com. If you’d like to get a spot at early bird pricing, register here.

Love this so much. “ . . . we can only see what we already recognize.” Going to try interviewing a few of my own recurring images.