The Erotic Principle: A Continuation

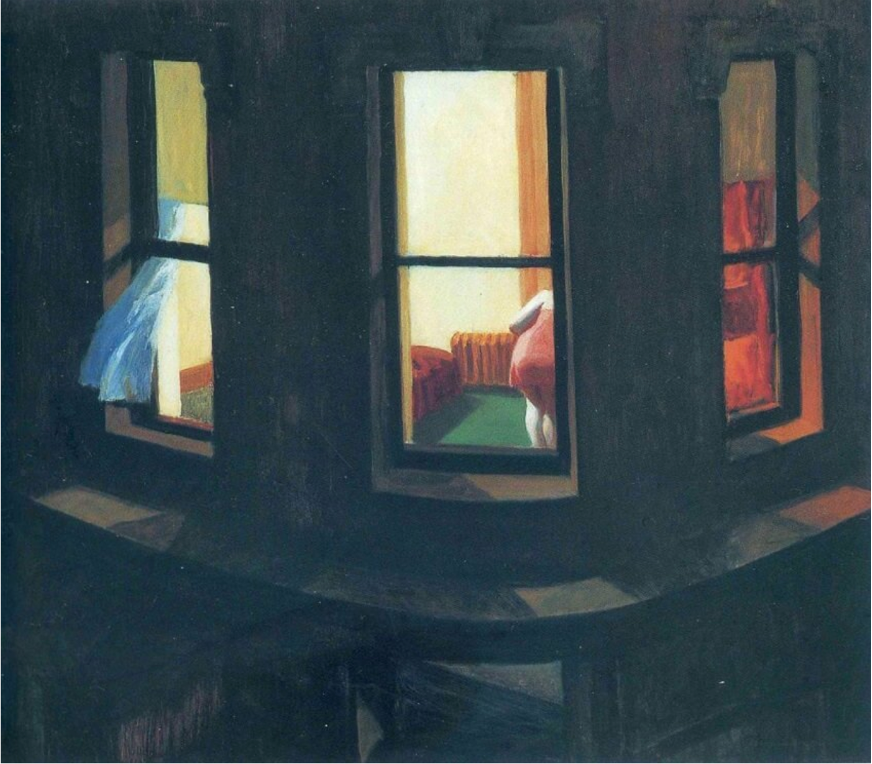

On flirty poems, a sonnet by Denis Johnson, and Edward Hopper

Hello Friends,

Edward Hopper once said, “If I could say it in words, there would be no reason to paint.” I’ve been thinking about that. The world has felt especially volatile this past week. When language fails, what’s there to do but turn to art?

I assume Hopper meant that visual art captures what language cannot. But of all modes of writing, poetry comes closest to reaching the most remote cliffs of language. Hopper is commonly described as a painter of silence, of streets and rooms with few people sharing space in stillness. Writing can convey silence, but a painting captures it in a more immediate way.

A painting reveals itself at once. We see the big picture, then our eye travels towards the details. A poem, on the other hand, opens slowly, line by line. But it’s not just what a line says; its movement is what matters. As we move through a poem, our mind and senses respond.

If a poem is to elicit desire, it must first give something, then take it away. This is counterintuitive but stay with me. Think of flirting. When we’re attracted to someone, we first build a connection, and once we’ve established a kind of stability, we signal romantic interest. A flirtation is a risk. We make a step, pause a little, then take a bigger risk. That see-saw between stability and instability feeds desire.

Have you ever watched a baby reach for a toy that her father is waving? The baby wants the toy, grasps it, and when the father pulls the toy back, the baby screams and laughs. The game intensifies her desire.

Something similar happens in a poem where different elements work together to establish patterns and then depart from them. Regardless of what the poem is about, it’s the design, from structure down to the path of the sentence, that builds desire in a reader.

In “Muscularity and Eros: On Syntax,” Carl Philips explains that at its core, poetry is simply “patterned language.” He says,

“The relationship between pattern and the meaningful disruption of that pattern gives poetry the muscularity required to become memorable. The careful calibration and manipulation of this relationship is . . . the definition of what seems to be meant by ‘the art of poetry.’”

He goes on to compare a poem to a body and the movements in a poem to the shifting of muscles in relation to each other:

“It all comes down, I believe, to the patterns established and disrupted within the poem at the level of, in particular, syntax, grammar, tense, point of view, sentence length, line length, and sound–which includes rhyme, meter, assonance, and alliteration.”

I think of this in relation to the erotic principle in poetry, which I wrote about in an earlier post.

What principles does a poem establish, and how does it betray them? How are rules set up and then subverted in ways that are thrilling? What risk does a poet take to make us feel as if the poem might crash? How is the poem prevented from going on an autopilot? A flirty poem, or one that I’d call erotic, is never predictable.

Here are some of the ways a poem might be flirting with us:

Look for structural shifts. Structural disruptions create charge.

Look for grammatical shifts.

Look for change in the logic of line endings: if most of the lines are complete grammatical units, they make sense when read on their own. How do the lines that don’t allow for the pause at the end, when they run straight to the next, affect the momentum?

Look at syntax. What is subordinated in a sentence? (Think top vs bottom dynamic.)

Look at sentence length, the ratio of tension and release.

Look at language density; look for breaths.

Listen to the music, echoes, and how the patterned sound is interrupted.

Look for rupture.

Denis Johnson’s “Heat,” is one of my favorites. Its pacing, sensual imagery, and especially the rhythm, from a smoky slowness at the start to the sharp freefall at the end, all create a visceral sensation of desire.

Here in the electric dusk your naked lover

tips the glass high and the ice cubes fall against her teeth.

It's beautiful Susan, her hair sticky with gin,

Our Lady of Wet Glass-Rings on the Album Cover,

streaming with hatred in the heat

as the record falls and the snake-band chords begin

to break like terrible news from the Rolling Stones,

and such a last light—full of spheres and zones.

August,

you're just an erotic hallucination,

just so much feverishly produced kazoo music,

are you serious?—this large oven impersonating night,

this exhaustion mutilated to resemble passion,

the bogus moon of tenderness and magic

you hold out to each prisoner like a cup of light?

Jay Deshpande discusses the poem in wonderful detail in this article, but I wanted to highlight a few things that relate to this idea of desire.

· Destabilized intimacy

The opening is a post-coital scene. The first line begins with “here” and ends with “your naked lover.” Starting with “here” puts emphasis on place, the room. The “naked lover” is on the other end of the line. This creates an oppositionality, a kind of magnetic polarity. We’re directly in the scene.

The next line pulls us in closer; she takes a drink, ice cubes clinking against her teeth. She, the lover, looms large. As a reader I’m seduced by her presence. She’s naked, beautiful, her hair is loose and “sticky with gin,” and her nickname “Our Lady of Wet Glass-Rings on the Album Cover” is highly suggestive. “Lady” elevates her. “Wet Glass-Rings” is, well, wet, and hints at rhythmic repetition.

But just when I think I know where this is going, the poem pulls the rug from under my feet. The lover is “streaming with hatred.” What felt like a mad promise is suddenly made unstable.

· Ruptured structure

This is a sonnet composed of two sestets and a couplet in the middle. It rhymes, albeit subtly, and there’s a volta, a turn where the poem pivots from one idea to another. That’s all standard sonnet architecture. But in this piece, the volta isn’t a gentle shift. In line nine, Johnson suddenly, out of the blue makes an address to—the month of August! And he delivers a bitter accusation at it, “you’re just an erotic hallucination.” Here, the poem doesn’t shift, it fractures.

The line visually breaks open. The point of view changes from third to second person. The mode changes too; we go from scene to voice and from description to rhetorical question. This volta strikes a match in the word “August,” finds a can of gasoline in the white space, and lets the rest, “you’re just an erotic hallucination,” blaze across the line.

It’s a strange, thrilling move. The poem continues in that mad talk, and by the end of the sentence, when it says, “Are you serious?” comes close to its own destruction.

· Erotic syntax

The poem consists of only three sentences: the first one is a taut, unadorned, two-liner. The second one stretches across six lines like a lazy cat. Together they create one long lush description. The final sentence is a six line long question; actually, it is two questions nested into one. We switch from descriptive mode to an exasperated address, “Are you serious?” which short-circuits the buildup. Johnson’s syntax mimics the movement of desire. It starts in a direct short step, then expands, and finally explodes.

· Volatile language

The last four lines that follow the rhetorical question are an escalation, a build-up of frustration with inability of true intimacy. Phrases such as “exhaustion mutilated to resemble passion” and “bogus moon of tenderness” are complex and dramatic. The speaker is “a prisoner” to desire. These metaphors are exaggerated to the point of parodying romantic language. They make me feel dizzy, excited, and by the end, the poem sounds like laughter and cries, both normal responses to frustration.

By the end, Johnson has disrupted so many elements of the poem, yet the piece doesn’t disperse in chaos. Volatility is its language and its erotic pulse. There is pleasure in these surprises. The poem risks its own demise and then lifts off, in a stunt-like way. I love how disappointment and pleasure mix here. The language sizzles with paradox, the “electric dusk” for example, combining softness of dusk with sharpness of electricity, and the tension, which at first beats under the surface like opening chords in a blues song, builds up, and erupts. And that question mark at the end? It’s like the intensifying chokehold.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

According to Matt Becker, Edward Hopper carried this quote by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in his wallet:

“The beginning and end of all literary activity is the reproduction of the world that surrounds me by means of the world that is in me, all things being grasped, related, re-created, molded, and reconstructed in a personal form and original manner.”

For both Goethe and Hopper art begins with the external world, which is then refracted through the artist's interiority. Hopper once also said, “I’m after me,” suggesting that his work was a search for self-understanding.

It makes me wonder, how much of any artwork is just that, a search for self, by both artists and viewers? The artist tries to understand themselves by making the work, while the audience seeks to meet their own selves through experiencing it. And if I sense desire in a poem, or in a painting, how much of that desire belongs to the artist and how much might it simply be my own response to what feels absent and unresolved in the work?

Starting October 8th, I’ll be teaching a 6-week advanced poetry writing workshop through Writers.com. If you’d like to get a spot at early bird pricing, register here.

❤️

Love this one! And especially love the “Mussels” painting👏👏👏