The Strange Effect of Geometric Forms

On transforming the world into shapes in painting and poetry

I recently started mastering the art of squinting. (Thanks, middle age!) Turns out blurred vision gave me new eyes. It’s dramatic, I know, to call squinting an art, but before you drift off, try it. Squint, and see the room you are in become simpler. Maybe your crush resembles a pocket knife, or your boss looks like a spinning top—small head, broad hips, tiny feet.

I’ll risk another big statement—before we notice shapes around us, we sense them in the body. When astrologers read charts, they speak of angles—harmonious trines, tense squares, potent conjunctions, itchy sextiles. When we glance at the skyline, we pick up on the clash of vertical buildings against the horizontal plane. Looking at the monochrome tranquility of a monk’s robe feels different than the frisky stripes of a pair of speedos.

The primary experience is always sensory. I have a mild case of synesthesia where touch and sound will trigger a kaleidoscope of fractals that expand and collapse in my mind’s eye. It’s partially why I like painting—the scribble, glide, rub and pour of the paint as I grasp for the inexpressible.

But without structure all that expression is just messy action. A fundamental aspect of any artistic expression is composition. It’s the arrangement of various elements in a piece. In painting, these include color, texture, value, shape, contrast, focal point, directional movement, and so on. To simplify, composition in painting is seeing the world in shapes.

Say you took a nice photo of a lake with some depth, and want to draw it. First, you’ll want to break the image down into the simplified shapes it’s constructed of. You can do this in two ways.

1. You can squint, close one eye and half shut the other. As the details disappear, parts of the photo will become clearer by tone, color and hue, and they’ll automatically create shapes. You might see a rectangle lake, cylinder trees, an oval boat, and free form clouds. Also, groups of objects will form new shapes. A single tree might become a patch of trees with a shadow stretching onto the lake, all together forming a dark languid oval.

2. Or you can use your phone’s editing tools and play with color saturation and contrast to make shapes stand out more clearly. The idea is to let the primary contours pop out.

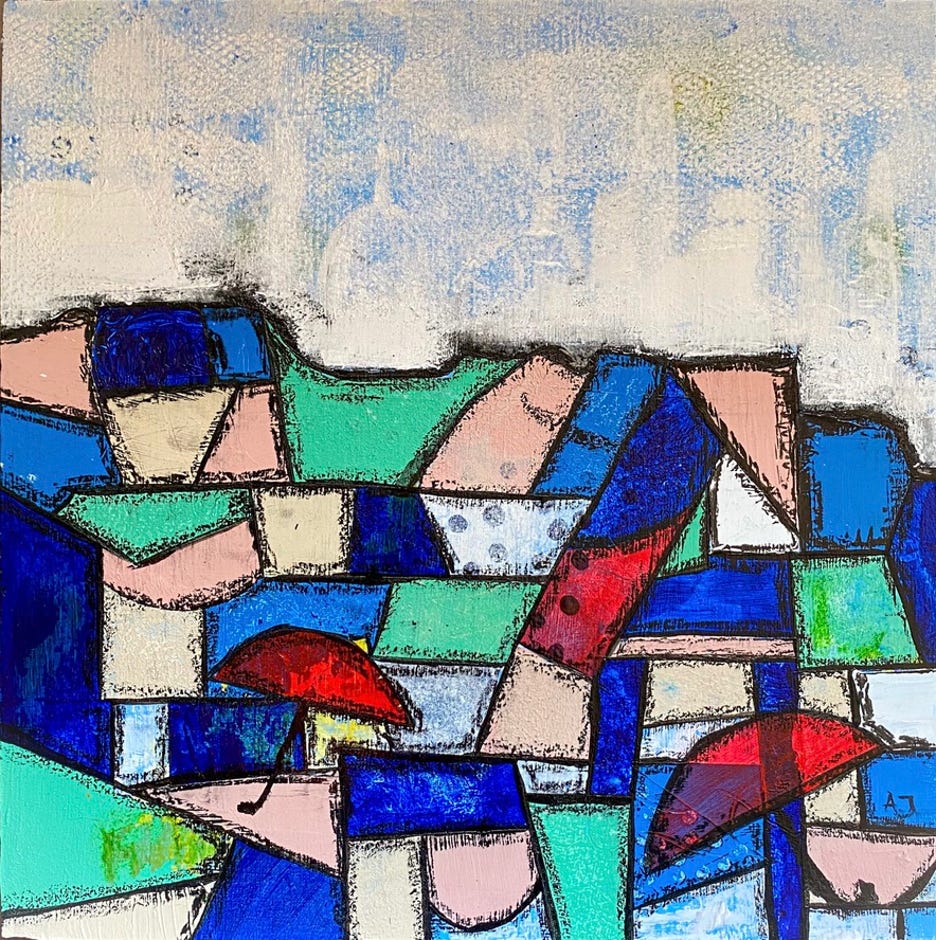

Breaking the world down into simple shapes is a start. Consider, for example, how the multiple perspectives of Cubism allowed artists such as Picasso and Braque to portray objects from various angles at once. Their paintings look like fragmented depictions of objects with the anarchy of shattered geometrical shapes in the background. They seem to move from the exposed order of the object’s body into incomprehensible shards of background space.

On the other hand, there are the Impressionists and the shifting optics of their paintings. They captured the world by focusing on the nuances of light, the trembling surfaces of the planes instead of the planes themselves. They make us aware of how our perception of objects, especially color, changes with the weather. Something similar happens when we photograph a piece of paper under different light bulbs. A soft white bulb renders the page in a yellowy cast while a bright daylight bulb shows the paper in a blue-bright crispness.

Poets are committed to seeing the world in new ways, too, so much so that the language used when talking about poetry is often similar to painting. Without knowing the context, we wouldn’t know whether words such as rhythm, movement, abstraction, sensory appeal, collage or ambiguity refer to a poem or a painting.

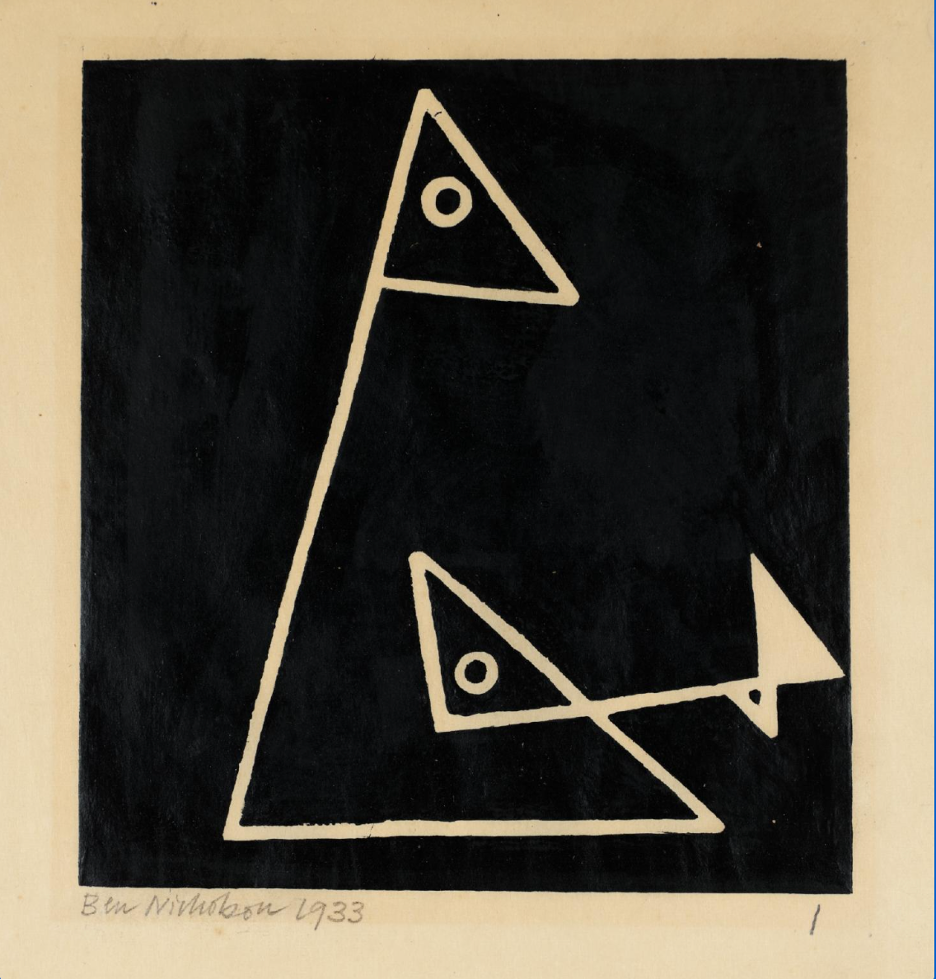

And poets have drawn more than a few techniques from art, especially abstract art. But sometimes one will apply a painterly composition technique quite literally. Here is a piece by John Ciardi that truly leans into this approach.

Elegy in a Cube

The triangle in the corner

Weeps for the circle in the base

Three ellipses lean over the circle,

Bend, and are lost looking.

The tears of the triangle

Are a separation. It was once

Contained in the circle. Locked in the base

The circle withdraws to its center.

The cube is of course at rest. It

Contains these figures wholly. It contains

Its own stability. But the tears of the triangle

Must take the form of their falling.

The ellipses bend to approach

The circle. They are already

Warped from their planes. But the triangle

Must suffer its own difference.

These forms in a world of form

I found in the strictness of tears

At a withdrawal of time. A holy family

In the dark of my own world’s warping.

In the namelessness of the real

I was entered by these ellipses

And, lost in their looking, I saw in every grave

The circular mother of the triangular man.

This poem obviously uses the language of geometric shapes. Of course this is an elegy; few things other than death change how we see life. And here grief is a lens through which the scene breaks into simple shapes: the man in mourning with elbows on knees and face in hands that is a triangle; the room that is the cube; the circle that is the mother; the base that is the coffin; the ellipses that are figures bent over the body of the mother.

It's interesting that the mother is presented as a circle, a shape that suggests cycles, embrace, completion. Triangles on the other hand bring to mind philosophical and religious triads like body-mind-soul or life-death-rebirth. And cubes are balanced no matter what goes on within them. The only element that’s not referred to by its shape is the tear. "The tears of the triangle,” the poem says, “Are a separation.” And that tear, and its anomalous organic shape, creates a hanging suspension in the poem.

Poetry, like squinting, helps us see things differently. And using painterly approaches extends our poetic sensibilities. So how might someone look at a poem like a painter? Here are a few ideas that come to mind. I’d love to hear yours, too.

1. Note any repetitions—sound and image patterns, or families of metaphor. Is there variance in it? How does the pattern and the variance feel in your body?

2. What is the underlying design of the poem? Does the poem circle from the end to the beginning? Does it snake, or follow the rule of thirds? Does it endlessly click-clack in unresolved couplets? What about dropped lines? How do they make you feel?

3. How are tonal shifts working here? How do they draw the eye?

4. Does the poem have enough contrast for you to experience depth and energy? If there was less contrast, how might those variations guide you?

5. How does the poem’s visual treatment on the page add significance to the piece? How does looking at the poem make you feel?

Love,

Andrea